Final Fantasy IV: The Complete Collection: the JRPG singularity

The first Final Fantasy was very different from what would be released little more than a year later as Final Fantasy II in America (and is properly known as Final Fantasy IV). People misremember how open the original was, your progress was always gated in the world by very specific choke points even if the game didn’t always tell you where to go next, or why. And while you were able to create your own party of characters, you still never made any decisions that affected the game’s outcome. Final Fantasy IV used that linearity to craft a much tighter, more resonant story. It also eliminated the character creation and substituted a large cast of well defined characters around whom the narrative revolved.

In Japan this was an evolution that took four years and four games, but for the English audience there was little more than a year between the two releases. The change was stark and shocking. By this time the Japanese role-playing game had strayed very far afield of the computer or pen and paper that had once been the inspiration. More than any game before it, Final Fantasy IV placed character drama at the forefront. The result was perhaps the most influential game the genre has ever seen.

After the jump, the primordial ooze from whence all JRPGs are descended.

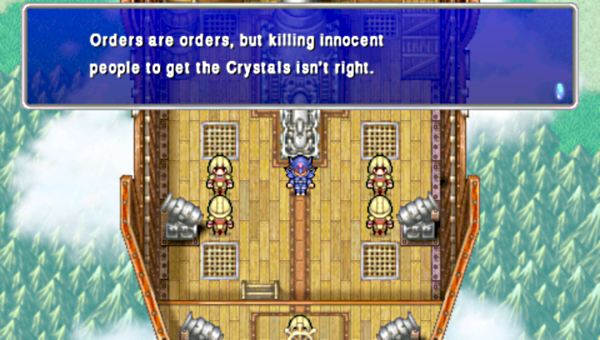

As Final Fantasy IV opens you watch Cecil, the character you will be playing the rest of the game, massacre a village of innocent mages and stealing a sacred magical artifact. This does not sit well with the other Red Wings, the elite airship crew Cecil commands. They complain that their orders have of late seemed more and more questionable. Cecil has misgivings of his own and brings his concerns before the his ruler, the King of Baron.

The King is not pleased to have his orders questions and strips Cecil of his command. He then gives Cecil a new mission, to deliver a package to the nearby village of Mist. Cecil travels there with his friend, Kain, a dragoon, but upon their arrival a horde of monster spring forth from the parcel and kill everyone in the village, save a young girl.

Within the first hour of the game you’ve already decimated two communities. Sure, you were acting on orders or unwittingly duped into the role of a suicide bomber, but it’s a very dark place to begin the tale. The rest of the game traces Cecil’s journey of redemption as he seeks to eradicate the darkness he carries inside himself and uncover the nefarious plot in which he has thus far been only a pawn.

Along the way Cecil will meet many complex characters, each with their own motivations and pieces of the puzzle. What’s most impressive is how tightly each character’s abilities are tied in to the overall narrative. Cecil is a Dark Knight who can’t hope to overcome the encroaching evil when his powers are derived from the same source. The old sage Tellah has forgotten more spells than he can remember, but he cannot avenge the death of a loved one unless he can find a way to recall the most powerful magicks. Rosa, the white mage is a healer, but when she is stricken by a rare disease it is up to her friends to find a cure.

Games in the series leave your party’s class and capabilities are largely up to the player. Final Fantasy V used a jobs system that let you develop each of the four main characters by building up levels in a variety of classes and then mixing and matching active abilities. This allowed for lots of fun experimentation and min/maxing, but it also placed severe restrictions on the story, as the number of playable characters was fixed and the kind of rotating cast IV employed was not feasible. One of the primary complaints against Final Fantasy VII was that the Materia system for character development meant that every character was a blank slate you could build towards any skill-set you wanted. Normally that would not sound like a bad thing, but it could lead to situations incongruous with the narrative being presented. While the story is telling you how demure and sensitive Aerith is, she could be your most powerful fighter, or you could take tough guy Barret and turn him into a squishy magician.

The lesson everyone in the industry seemed to take was that players like a well crafted, linear narrative, but in the rush to follow in that vein the calculated alchemical relationship between Final Fantasy IV’s characters, story and gameplay have too often been overlooked. What followed is a litany of games, from Square-Enix, and other developers, that reuse ideas, visuals and mechanics from Final Fantasy IV, so much so many have become JRPG tropes. Many have even been good, but few truly live up to their progenitor.

Final Fantasy IV’s singular genius is in the balance it struck. Any deficit in character customization it may have, it more than makes up for with inventive scenarios designed to exploit the ever changing party lineup and engage the player with new strategic challenges at each turn. It’s a game rich with melodrama, introspective scenes under the stars, betrayal, doubt, tragedy and sacrifice. There is an emotional core to each dungeon you’ll plumb, each boss you’ll face. Oh, and you’ll also get to visit the moon.

Up next: Exactly how many times will I buy Final Fantasy IV?

Click here for the previous Final Fantasy IV entry.

Brad Grenz lives in the beautiful Pacific Northwest. He writes fake biographies about real bands, blind reviews of games he hasn’t played, and makes good use of his degree in Philosophy eking out a living in web design.